Zero-Knowledge Virtual Machines (ZKVMs) in Practice: A Technical Survey

Zero-knowledge virtual machines (ZKVMs) are proof-generating replicas of familiar software stacks. After running a Rust, C++, or Move program once, the ZKVM will produce a compact receipt that anyone, even a smart contract with limited computational resources, can check in milliseconds.

Because they turn heavyweight replays into quick proof checks with optional privacy, ZKVMs already anchor privacy-preserving DeFi flows, compliance attestations, oracle feeds, and rollups that need to prove arbitrary business logic without rewriting everything as circuits.

In writing this piece, we will focus on the following engineering-related details:

- Show why reusable ZKVM pipelines matter through a concrete, game-style workload.

- Decompose the end-to-end pipeline from high-level code to verifier-facing proof objects.

- Detail the Algebraic Intermediate Representation (AIR) construction tricks, lookup-heavy opcode handling, and offline RAM arguments that keep constraint counts linear.

- Explain how modern proving stacks shard, recurse, and orchestrate proofs so that large traces finish within real-world latency budgets.

1. ZKVMs Use Case - A Toy Example

A representative example comes from zkSync’s “Build a ZK Game” tutorial, which walks through the process of porting a simple arcade title into a verifiable experience. In this setting, players prove that a sequence of inputs, such as the paddle moving in Breakout or jumps in Only Up, necessarily leads the game engine to the claimed score. Observers need only check the proof; they never replay the full game or trust the player’s screenshots.

To produce that proof, the game logic must still be executed inside a circuit. However, hand-writing bespoke circuits for every game variant is tedious and brittle. A ZKVM side-steps that burden by automatically compiling the existing Rust or C++ implementation into a circuit, ensuring execution remains provably correct and deterministic.

Although this gaming example is intentionally lightweight, it highlights why general-purpose ZK compilation is essential. Without a reusable compiler pipeline, each new workload would require bespoke circuit engineering, and the correctness gap would widen over time. Rollups, privacy-preserving compliance pipelines, oracle bridges, and countless other workloads all want the same guarantee: to reuse conventional software stacks, but emit proofs that anyone can verify succinctly.

2. ZKVM Pipeline Anatomy

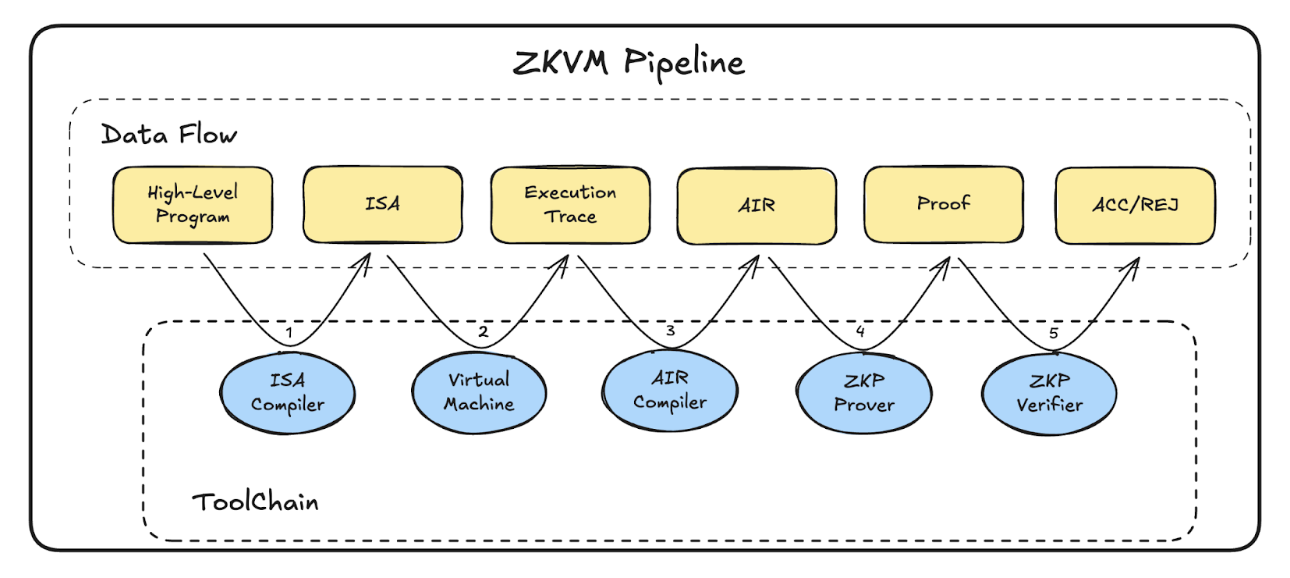

Every ZKVM ultimately proves that “this high-level program ran correctly”, but the proof object only sees algebra. The pipeline below explains how we shuttle code through progressively more structured representations while preserving determinism of program execution and completeness at each step.

- ISA Compiler: Guest code (Rust, C++, Move) is lowered into a prover-friendly instruction set architecture (ISA) such as RISC-V (RISC Zero, Succinct SP1, ZKSync Airbender). This stage fixes the instruction set and removes undefined behavior so that later phases have a deterministic transcript to reason about.

- Instrumented VM Execution: The compiled binary runs inside a zk-friendly VM that logs an execution trace, including per-cycle opcodes, operands, memory accesses, and I/O commitments. These traces are the authoritative witness; if they drop a register or misorder a memory event, the trace will fail to prove.

- AIR / Constraint Compiler: The trace feeds an Algebraic Intermediate Representation that encodes transition rules, memory-consistency hooks, and public-input wiring.

- Prover Backend: General-purpose proving stacks (Plonky3, Stwo) consume the AIR. They know nothing about the original program; their job is to convince a verifier that every constraint holds. Implementations often shard witnesses or pipeline sub-circuits here to stay within memory budgets.

- Verifier / Wrapper: The prover’s sibling verifier (plus any recursive/outer SNARK wrapper) checks the final proof and exposes a succinct accept/reject interface to chains, bridges, or auditors.

Two pressure points dominate: designing the AIR so that it captures correctness without exploding in size, and orchestrating the prover so that significant traces fit in memory. The next sections dive into those engineering trade-offs, the lookup-heavy AIR design, and the required architecture to prove massive traces at constant cost.

3. AIR Compilation

3.1 A Straightforward Solution

The native language for most backend provers is an arithmetic circuit, so that AIR compilation effectively replays the entire program inside a circuit. The key advantage is that the circuit can receive auxiliary witness data, making verification cheaper than re-executing every instruction within the arithmetic constraints. A canonical example is checking a square root: instead of recomputing

ZKVM AIR compilation applies the same trick. The full execution trace serves as a rich witness, so the circuit simply verifies that adjacent machine states are consistent rather than recomputing them from scratch. That framing opens up optimization opportunities: the OpenVM, RISC Zero, SP1, and ZKSync Airbender white papers all detail slightly different arithmetizations built on this template.

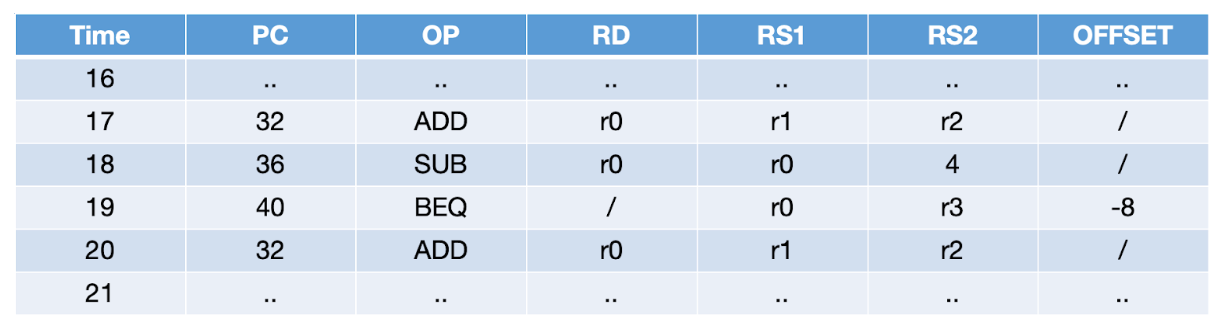

Consider the truncated trace below:

Each row includes the timestamp, program counter (PC), opcode, destination register (RD), operands (RS1/RS2), and offsets. The circuit must assert that every instruction obeys the ISA transition rules. At timestamp 17, we enforce that the ADD result in r0 equals r1 + r2 and that the PC advances by four bytes. At timestamp 19, we check the equality predicate and conditionally set pc -= 8. AIR generation, therefore, feels “straightforward,” but two circuit-specific pain points dominate the cost profile:

- Opcode Selection at Circuit Speed: A naive encoding evaluates every possible opcode branch per row. If one branch is significantly heavier (e.g., a custom hash gadget), the entire circuit inherits that cost even if the opcode rarely appears.

- Lack of True Random-Access Memory: Naively modeling RAM forces each read/write to reference every possible address with boolean selectors. With

NVM steps andMmemory slots, you end up wiringN × Mselector bits, so the constraint system grows quadratically unless you swap in permutation-style memory arguments.

Sections 3.2 and 3.3 outline the standard mitigations.

3.2 LookUp / LogUp Arguments to Sidestep Opcode Selection Overhead

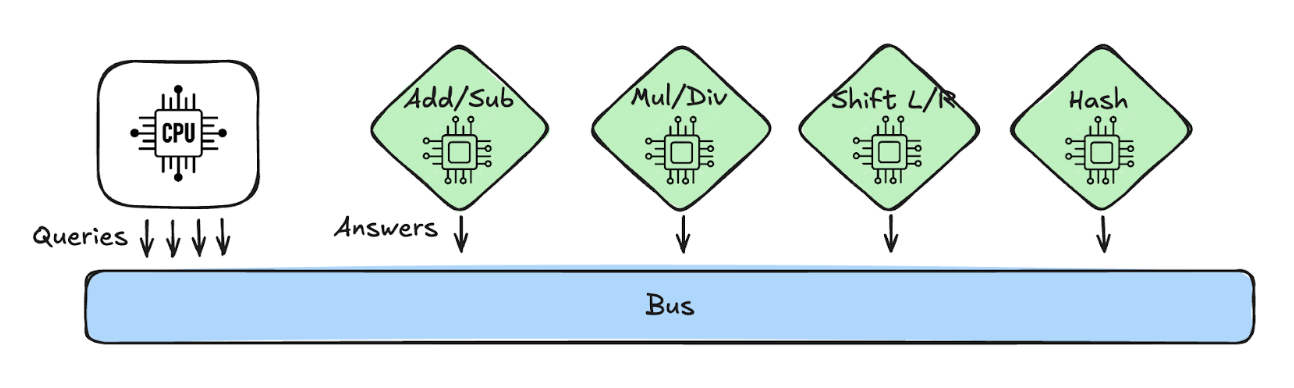

Straight-line AIRs pay dearly for branching: if a row has to evaluate every opcode branch, the heaviest gadget dominates the cost. Lookup arguments copy the CPU/ALU split from hardware, log the request in the CPU trace, prove the heavy math elsewhere, and only check that “this row queried that table.”

OpenVM pushes the idea to the extreme by even outsourcing PC updates to opcode-specific “chips,” so integrating new opcodes means wiring a new table rather than touching the CPU core.

- Emit tuples: Each instruction in the CPU records a tuple such as

(opcode_id, operand_0, operand_1, result). - Replay in coprocessors: Dedicated chips (hash cores, modular arithmetic gadgets, range check tables) replay the tuples addressed to them, enforce the actual opcode semantics, and commit a table of

(opcode_id, operand_0, operand_1, result)rows. OpenVM’s approach means even PC updates can be handled here. - Run the lookup: Given commitments to both the CPU query log and the coprocessor tables, the bus runs a lookup argument to ensure every query exists in some table with matching values.

LogUp Refresher

The LogUp argument replaces the typical grand-product with logarithmic sums. It checks that the multiset of queries {q_i} matches the multiset of table entries {t_j} with multiplicities m_j via

where X is a random verifier challenge. Queries and table rows are randomly combined into field elements r_0 * opcode + r_1 * operands + r_2 * result) before entering the check, and Fiat–Shamir turns the interaction into a non-interactive proof. LogUp avoids large products, which is more friendly to circuit arithmetization.

Advantages and Trade-offs

Lookup buses collapse thousands of per-opcode constraints into a few inclusion checks. The trade-off is additional commitments: you now commit to the query log and to each coprocessor table.

3.3 Offline Memory Checking

Opcode lookups tame branching, but memory remains the other major pressure point: we must convince the verifier that every load observes the latest store without wiring an entire RAM array into the circuit. ZKVMs handle this by decoupling execution from memory consistency—each access is recorded on a “memory bus,” and the resulting log is checked with a permutation or multiset argument once the trace is complete.

The construction most teams lean on dates back to Blu+91. Below is the high-level recipe.

- Emit the footprint: Whenever the VM touches memory it logs a tuple

(ts (timestamp), is_read, addr, v (value)). The circuit defers all coherence checks until it has the full list. - Offline Check: ZKVMs derive two sets as the send set

SS,and the receive setRS. A memory footprint, either read or write, will update both these two sets per the following rules:- Read:

(ts, addr, v). Adding(prev_ts, addr, v)to theRS, and(ts, addr, v)to theSS, whereprev_tsis the last time that location was accessed, which is supplied as additional witness and must be smaller thants. - Write:

(ts, addr, v). Adding(prev_ts, location, prev_v)to theRS, and(ts, addr, v)to theSS, whereprev_vis the value at that location before being overwritten.

- Read:

And then we simply prove set equality.

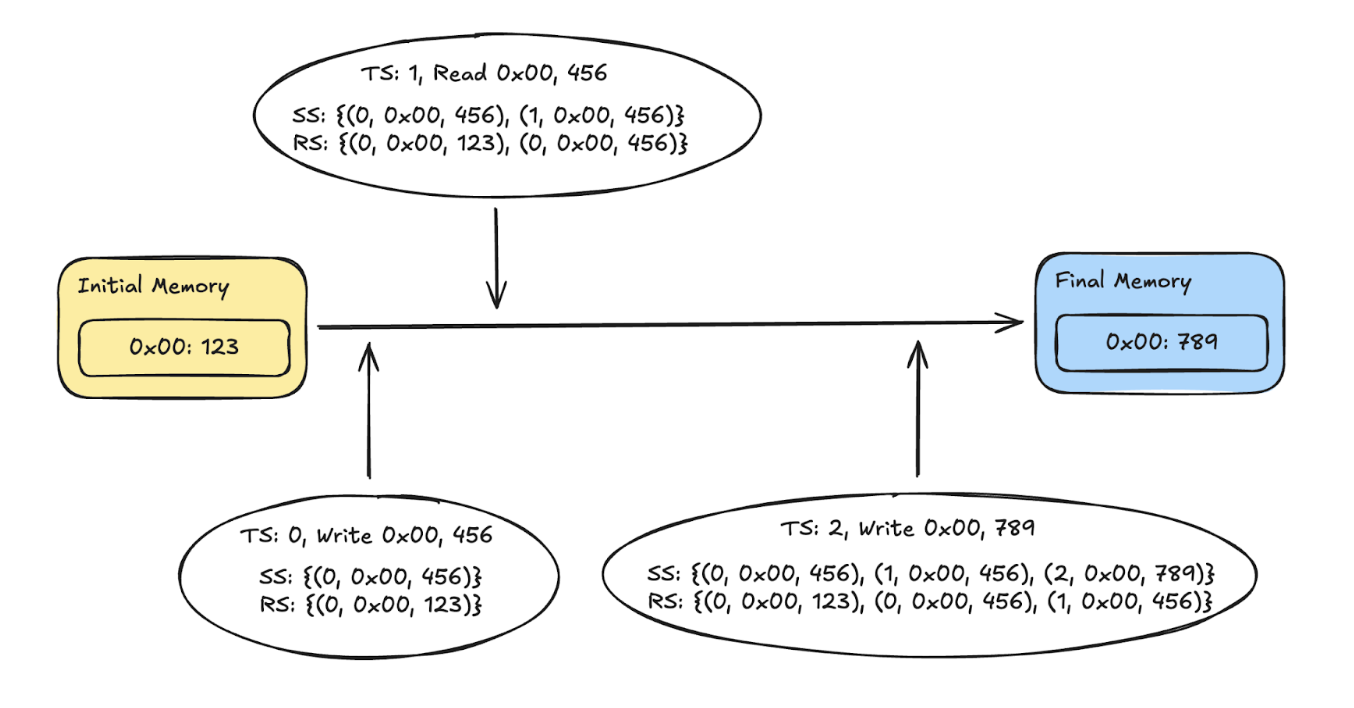

Example

Consider a single memory slot 0x00 with three consecutive operations: (0, Write, 0x00, 456), (1, Read, 0x00, 456), (2, Write, 0x00, 789). As the log is processed, RS and SS fill with matching tuples; by timestamp 2, almost every element cancels, leaving the initial and final memory contents to bridge the remainder. The figure below illustrates the running state of both multisets.

Circuit Friendly

The argument is circuit-friendly in the sense that, given the initial memory and memory footprints, the RS and SS can be easily generated within the circuit, and the prev_ts, prev_v, and final_memory can be supplied as additional witnesses with proper checks. There is almost no overhead except the required commitment to the memory footprint.

4. Proving Architecture & Performance Levers

Up to now, the prover was a black box: feed it AIR, receive a proof. Real deployments hit two practical limits long before the math does—memory pressure (the trace does not fit in a single circuit) and latency (operators need proofs in seconds, not hours). Modern ZKVM stacks, therefore, treat proving as a distributed systems problem. They split traces into chunks, schedule them across heterogeneous hardware, and then fold the resulting proofs back together so the verifier still sees a single artifact.

Concretely, the execution trace is cut into trunks with three guarantees:

- Local correctness: each trunk proves its own instruction slice against the AIR.

- Boundary consistency: consecutive trunks agree on PC, memory commitments, and any public I/O.

- Shared public state: every trunk commits to the same code image and public inputs, preventing “trace splicing” attacks.

Those chunks can be proved in parallel or streamed from disk, but they generate multiple proofs that must be reconciled.

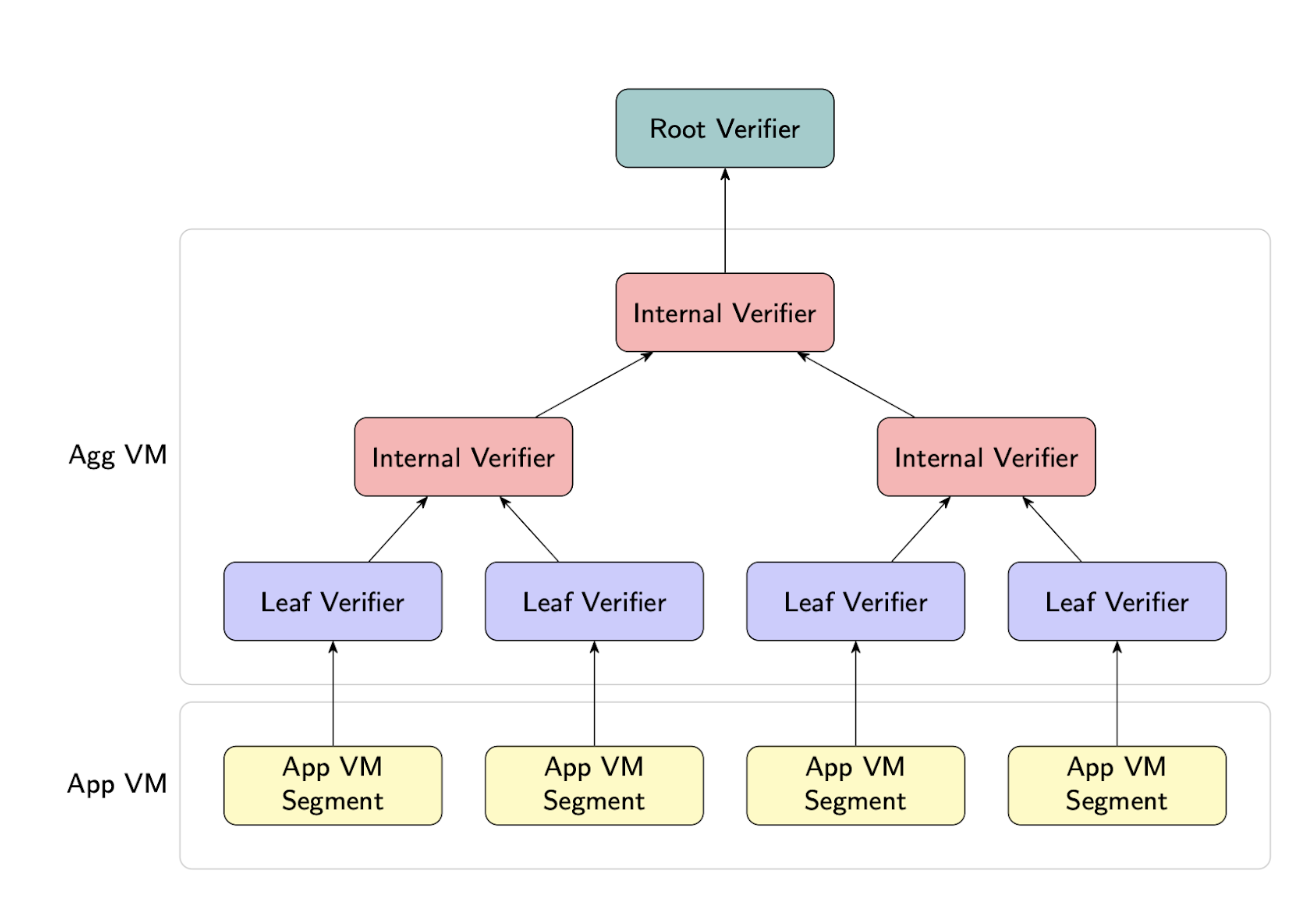

4.1 Proof Composition and Recursion

Without aggregation, verifiers pay linearly in the number of trunks. Recursion solves this by embedding the verifier logic of child proofs within a parent circuit, producing a single “wrapper” proof whose verification cost remains constant. The OpenVM white paper illustration below shows the binary-tree pattern most projects adopt:

Once the recursion tree produces a single proof, teams often wrap it again in a succinct SNARK (Groth16, KZG-based PlonK) so on-chain verification stays constant-size.

These system-level levers, especially tuning how traces are streamed to heterogeneous hardware like GPUs, FPGAs, or other accelerators, frequently deliver bigger real-world wins than marginal AIR tweaks.

5. Summary

Production-ready ZKVMs reuse existing code by lowering it into deterministic VM traces, compressing opcode logic with lookup/logup coprocessors, and verifying RAM via offline permutation checks so constraint growth stays near-linear. Provers then treat the witness as a distributed workload, chunking traces, streaming witnesses to specialized hardware, and recursively folding subproofs, so final verifiers see a single, constant-cost artifact. The engineering frontier now lies in co-designing AIR layouts with recursion-friendly backends while tuning sharding, scheduling, and hardware placement to minimize wall-clock latency for million-cycle programs.

References

- Matter Labs, “Build a ZK Game Tutorial”.

- Jeremy Bruestle, Paul Gafni, and the RISC Zero Team, “RISC Zero zkVM: Scalable, Transparent Arguments of RISC-V Integrity”.

- Succinct Labs, “SP1 Technical Whitepaper”.

- Matter Labs, “zkSync Airbender”.

- OpenVM Contributors, “OpenVM White Paper”.

- Ulrich KaTeX can only parse string typed expression, “Multivariate Lookups Based on Logarithmic Derivatives”.

- M. Blum, W. Evans, P. Gemmell, S. Kannan, and M. Naor, “Checking the Correctness of Memories” 1991.